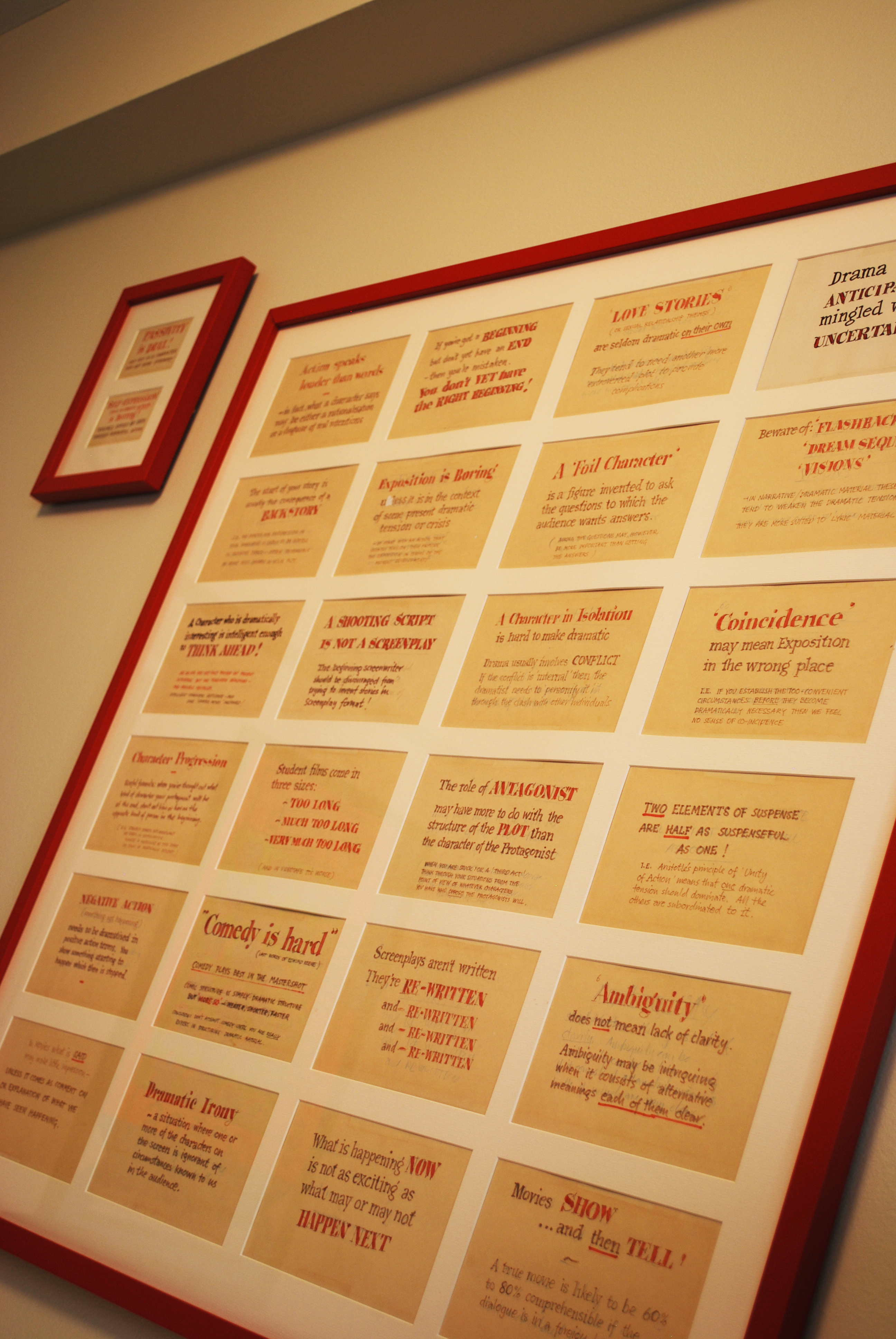

On Film-Making: An Introduction to the Craft of the Director

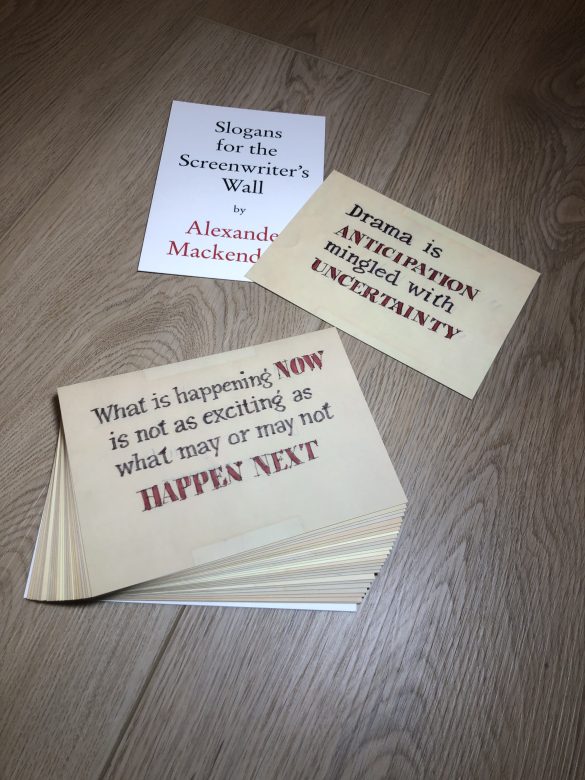

Slogans for the Screenwriter’s Wall

Movies SHOW… and then TELL. A true movie is likely to be 60% to 80% comprehensible if the dialogue is in a foreign language.

PROPS are the director’s key to the design of ‘incidental business’: unspoken suggestions for behavior that can prevent ‘Theatricality.’

A character in isolation is hard to make dramatic. Drama usually involves CONFLICT. If the conflict is internal, then the dramatist needs to personify it through the clash with other individuals.

Self pity in a character does not evoke sympathy.

BEWARE OF SYMPATHY between characters. That is the END of drama.

BEWARE OF FLASHBACKS, DREAM SEQUENCES and VISIONS. In narrative/dramatic material these tend to weaken the dramatic tension. They are more suited to ‘lyric’ material.

Screenplays are not written, they are RE-WRITTEN and RE-WRITTEN and RE-WRITTEN.

Screenplays come in three sizes: LONG, TOO LONG and MUCH TOO LONG.

Student films come in three sizes: TOO LONG, MUCH TOO LONG and VERY MUCH TOO LONG.

If it can be cut out, then CUT IT OUT. Everything non-essential that you can eliminate strengthens what’s left.

If it can be cut out, then CUT IT OUT. Everything non-essential that you can eliminate strengthens what’s left.

Exposition is BORING unless it is in the context of some present dramatic tension or crisis. So start with an action that creates tension, then provide the exposition in terms of the present developments.

The start of your story is usually the consequence of some BACKSTORY, i.e. the impetus for progression in your narrative is likely to be rooted in previous events – often rehearsals of what will happen in your plot.

Coincidence may mean exposition is in the wrong place, i.e. if you establish the too-convenient circumstances before they become dramatically necessary, then we feel no sense of coincidence. Use coincidence to get characters into trouble, not out of trouble.

PASSIVITY is a capital crime in drama.

A character who is dramatically interesting is intelligent enough to THINK AHEAD. He or she has not only thought out present intentions, but has foreseen reactions and possible obstacles. Intelligent characters anticipate and have counter moves prepared.

NARRATIVE DRIVE: the end of a scene should include a clear pointer as to what the next scene is going to be.

Ambiguity does not mean lack of clarity. Ambiguity may be intriguing when it consists of alternative meanings, each of them clear.

‘Comedy is hard’ (last words of Edmund Kean). Comedy plays best in the mastershot. Comic structure is simply dramatic structure but MORE SO: neater, shorter, faster. Don’t attempt comedy until you are really expert in structuring dramatic material.

The role of the ANTAGONIST may have more to do with the structure of the plot than the character of the PROTAGONIST. When you are stuck for a third act, think through your situations from the point of view of whichever characters OPPOSE the protagonist’s will.

PROTAGONIST: the central figure in the story, the character ‘through whose eyes’ we see the events.

ANTAGONIST: the character or group of figures who represent opposition to the goals of the protagonist.

DRAMATIC IRONY – a situation where one or more of the characters on the screen is ignorant of the circumstances known to us in the audience.

If you’ve got a Beginning, but you don’t yet have an end, then you’re mistaken. You don’t have the right Beginning.

In movies, what is SAID may make little impression – unless it comes as a comment or explanation of what we have seen happening.

What is happening NOW is apt to be less dramatically interesting than what may or may not HAPPEN NEXT.

What happens just before the END of your story defines the CENTRAL THEME, the SPINE of the plot, the POINT OF VIEW and the best POINT OF ATTACK.

Make sure you’re chosen the correct point of attack. Common flaw: tension begins to grip too late. Perhaps the story has to start at a later point and earlier action should be ‘fed in’ during later sequences.

What happens at the end may often be both a surprise to the audience and the author, and at the same time, in retrospect, absolutely inevitable.

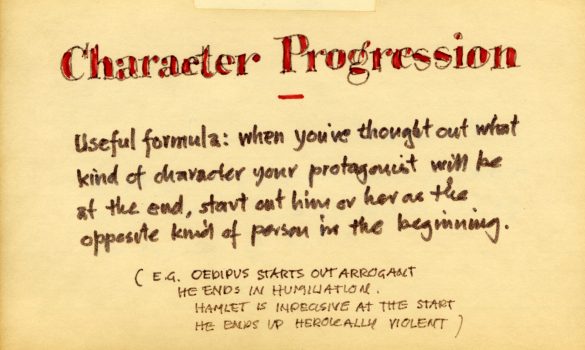

Character progression: when you’ve thought out what kind of character your protagonist will be at the end, start him or her as the opposite kind of person at the Beginning, e.g. Oedipus who starts out arrogant and ends up humiliated, Hamlet who is indecisive at the start and ends up heroic.

ACTION speaks louder than words.

Most stories with a strong plot are built on the tension of CAUSE AND EFFECT. Each incident is like a domino that topples forward to collide with the next in a sequence which holds the audience in a grip of anticipation. ‘So, what happens next?’ Each scene presents a small crisis that as it is revolved produces a new uncertainty.

DRAMA IS EXPECTATION MINGLED WITH UNCERTAINTY.

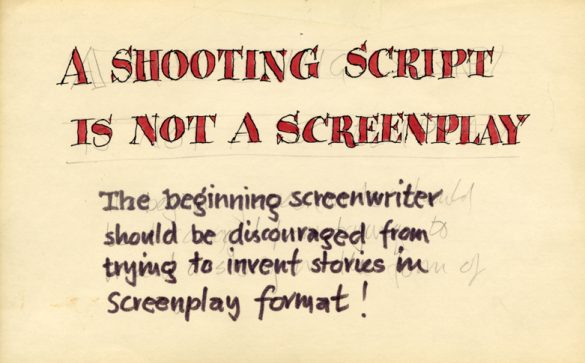

A SHOOTING SCRIPT IS NOT A SCREENPLAY. The beginning screenwriter should be discouraged from trying to invent stories in screenplay format.

A FOIL CHARACTER is a figure invented to ask the questions to which the audience wants answers (asking the question may be more important than getting the answer.)

NEGATIVE ACTION (something not happening) needs to be dramatised in positive action terms. You show something starting to happen which then is stopped.

TWO ELEMENTS OF SUSPENSE ARE HALF AS SUSPENSEFUL AS ONE. Aristotle’s principle of unity means that one dramatic tension should dominate. All others are subordinate to it.

CONFRONTATION SCENE is the obligatory scene that the audience feels it has been promised and the absence of which may reasonably be disappointing.

What you leave out is as important as what you leave in.

Screenplays are STRUCTURE, STRUCTURE, STRUCTURE.

Never cast for physical attributes.

Every character is important.

© Mackendrick Family Trust