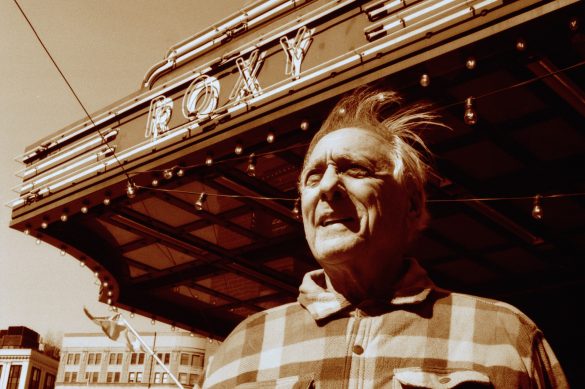

Paul Williams

Emissions, Omissions and Illustrations (2023), a monograph about the film director containing new and archival interview fragments and many images and documents, is a companion piece to his memoir Harvard, Hollywood, Hitmen, and Holy Men (University Press of Kentucky, 2023).

Emissions, Omissions and Illustrations (2023), a monograph about the film director containing new and archival interview fragments and many images and documents, is a companion piece to his memoir Harvard, Hollywood, Hitmen, and Holy Men (University Press of Kentucky, 2023).

Books about New Hollywood – the Golden Age of iconoclastic, bullish, generally untried young filmmakers stretching, more or less, from Bonnie and Clyde to Star Wars and the post-Vietnam War years – are a dime a dozen. Historians and critics continue to enthuse over an established canon, focusing on preeminent figures and films, while occasionally finding plenty of new paths to explore. Yet most authors can be excused for making not a single mention of a figure around whom, for a time, seminal members of the New Hollywood cohort – Brian De Palma, Terrence Malick, Bob Rafelson, George Lucas, Francis Coppola, John Milius, Jacob Brackman, Bert Schneider, Julia Phillips, Steven Spielberg, Martin Scorsese, Robert De Niro, Karen Black, Jack Nicholson – swirled.

The omission of Paul Williams – not “critically undervalued,” just made completely invisible, unwritten about to a spectacular degree – is understandable. He was up there with the biggest of them, off the blocks as early as anyone, nudging the summit in the era of the film director as superstar. But Williams’s cinema was never flashy (Molly Haskell said he “makes films under his breath”); he was provocative but not prolific (“I’d trust you with maybe two million,” Warren Beatty told him – not enough to make a big film); his three foundational features as writer–director – Out of It (1969), The Revolutionary (1970), and Dealing: Or the Berkeley-to-Boston Forty-Brick Lost-Bag Blues (1972) – remain largely unseen; his role as producer of early Malick and De Palma films has been eclipsed by his self-promoting business partner, Edward Pressman; and most people think that the Paul Williams who produced Phantom of the Paradise is the same songwriter/actor PW who appears in the film. (Quentin Tarantino’s book Cinema Speculation, making passing mention of Williams, reminds us not once but three times that our PW is not “the diminutive songwriter.”) If that weren’t reason enough why such a captivating story is so unexplored, Williams’s impulse has been, as he puts it, “to be less visible.” He has drifted always in “a different direction.”

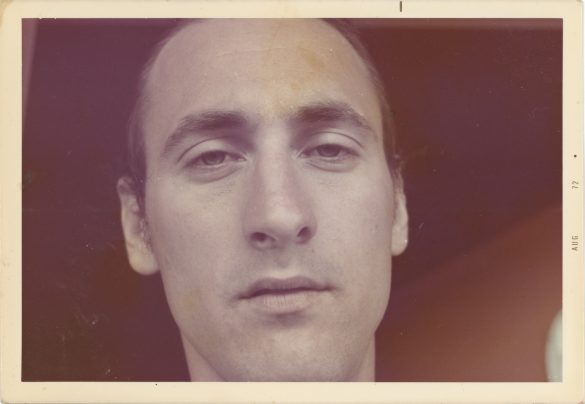

Born Paul William Goldberg in New York, he was thirteen when, in 1957, his autocratic, progressive high school principal father moved the family to insular Massapequa, Long Island. Murray Goldberg insisted Paul change his name before beginning studies at Harvard on a scholarship. Williams acknowledges the tragic absurdity: “Paul Goldberg commits hari-kari. Paul Williams now – if anyone finds out – is a covert, shameful, self-hating name-changing Jew.” (The joke, it turned out, was on Murray. “In the fall,” writes Williams in his insightful and frank memoir Harvard, Hollywood, Hitmen, and Holy Men, “I shall discover that of the 1,200 Harvard freshman, 400 are Jews.”)

At Harvard, where he studied with Rudolf Arnheim, John Kenneth Galbraith, Timothy Leary, B.F. Skinner, Erik Erikson, Reinhold Niebuhr and Henry Kissinger, Williams put his Argus still camera to good use, taking photographs for the The Harvard Crimson, including a cover image of JFK’s funeral. He made a documentary about life in rural France; co-wrote and directed Don’t Walk (1965), a slapstick short filmed on the streets of Cambridge and across the river in the Museum of Fine Arts; and created the ten-minute Crew (1965), the basis of which was his hundreds of Harvard rowing crew photographs. Over four undergraduate years (1961–64), Williams took classes with animation pioneers John and Faith Hubley and became an expert with an Oxberry Animation Stand. He was inspired by an encounter on campus with Jean Renoir and wrote about cinema for the Crimson (he recalls meeting Todd Gitlin – “a model of how to live your life if you were genuinely committed” – in the editorial offices), including an article about Robert Gardner’s new visual studies program. After achieving summa cum laude for his thesis, “The Expressive Meaning of Body Positions” (a version of which was published), he avoided the draft by going to Cambridge, England, for a graduate degree, where he ended up spending his tuition money on a final short, the existential Girl (1966), in which a young man, catching sight of a girl in a park, spins through in his mind a series of speculative flashforwards about what a lifetime with her might be. Did Boy just dodge a bullet, a lifetime of misery, or walk past the best thing that might ever happen to him? It’s Erikson’s stages of life in twelve minutes. Williams had a single roll of Eastmancolor and money only for a one-day camera rental. Every shot was filmed just once, and much of the musical story is told in still photographs.

The night before filming, at a party in London, Williams met Ed Pressman, and before their return to New York they formed a production company. (“Paul was the next Orson Welles and I was Irving Thalberg,” explained Pressman. “It was really through Paul that I got into film and gained the confidence to be a producer.”) Back home, David Picker at United Artists offered to buy a treatment authored by Williams – a riff on the psychological impact of Vietnam as “the living room war” – but the deal died when Williams insisted on directing. Failing to interest anyone else in the idea, he enrolled, along with Martin Scorsese, in graduate school at New York University but quit before classes began. Representative not of a squadron that graduated from film school and thence to an industry career, but an individual who gleefully jumped onto an already fast-moving train – that of “independence” – Williams was featured in a 1967 New York Times article about Ivy Leaguers now making films.

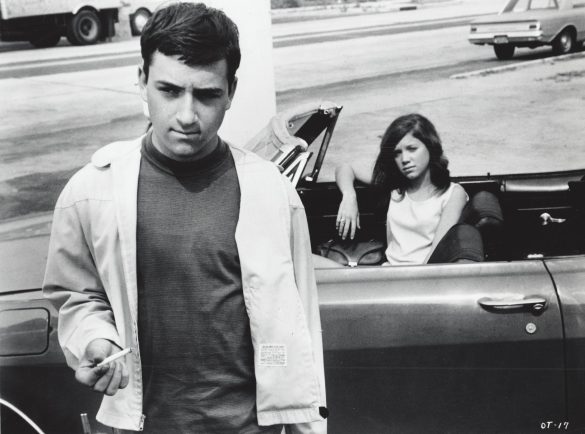

By December of that year, the month of Time magazine’s cover story on Hollywood fluctuations and the mainstreaming of unconventional cinema, Williams had finished postproduction on his debut feature, Out of It, which he described as “a simple but honest semi-autobiographical script about a sensitive kid in high school who never got laid.” He was twenty-three when he wrote the script and a year older when filming – on location on Long Island, including in Williams’s own bedroom, covered in W.C. Fields, Blow-Up, and Jean-Paul Belmondo posters – was completed. A coming-of-age beach comedy set during the waning Eisenhower years, the modest but aspirational Out of It is a prototype American Graffiti and classic New Hollywood: aesthetically adventurous (Godard/British New Wave imagery), self-referential (the final shot has Paul, played by Barry Gordon, stare knowingly into camera), financed out of pocket by Pressman then sold to United Artists on a negative pickup deal.

The filmmaking is simply done – Williams was more interested in working with actors and, quoting his friend Lindsay Anderson, in the “musical qualities” of his images. His avoidance of fancy camerawork was largely practical. Out of It, he explained in 1969, was shot in a “severe ‘classical’ style” so he wouldn’t have to rent a camera dolly. There are nice touches, like the scene at a Greenwich Village production of Romeo and Juliet, as Paul’s quickening heartbeat, in response to Christine, the girl of his dreams sitting next to him, is reflected in a speeding up of Shakespeare’s language. His Billy Liar-like reveries include Christine’s fantasies, as she pouts to camera: “Paul, you know so much – about nonviolence, Gandhi, Christ, Martin Luther King. Oh, how I love you! How I want to talk with you!” John Avildsen, credited as director of photography, who knew a lot more about filmmaking than Williams and Pressman, organised preproduction elements and was camera operator. Carl (12 Angry Men) Lerner assisted with the edit.

Filmed in 1967 and set six years earlier, Out of It is something of an elegy to a bygone era. But with its one-foot-in-the-future sensibility, it’s a positively explosive film, much more than a period piece. With his look to the lens, Paul lets us know that the forces holding him back are now visible to him – and so neutralized. Everyone, as R.D. Laing (an influence on Williams’s worldview) put it, is playing a game. But not noble Paul. Ready for what’s coming, for his next life experience, he has freed himself. The usual motivational systems no longer have control over him. The breaking of the fourth wall suggests audience complicity in Paul’s new understanding of the world. Similarly, the youth of America is developing its own code of ethics, a new way of talking, different styles of engagement. And come hell or high water, things are going to change. Jacob Brackman defined this pre-Graduate, pre-Vietnam, pre-assassinations historical moment: “There were no politics, no Beatles, no marijuana, no pill, no internationally publicized community of the alienated.” And yet, as Williams’s film makes clear, the community was there all along. Is it our nebbish anti-hero, or the constrictive suburban community where he lives, who are “out of it”?

One of the film’s strengths – a performance by up-and-comer Jon Voight, including a piece of glorious solo improvisation when his character has a (fake) gun pointed at him – became its biggest hurdle. When Voight won the role of Joe Buck in Midnight Cowboy (1969), an apprehensive UA decided to wait until after the release of John Schlesinger’s film before unleashing Out of It. Finally unveiled nearly two years late, at the end of 1969, Williams’s small-scale debut – in black and white, at a time when colour films had assumed dominance – looked like a homemade period piece with too much of an underground vibe. It got good reviews but did no business. George Stevens enthused over it in Berlin, until street protests shut down the festival before any prizes were awarded.

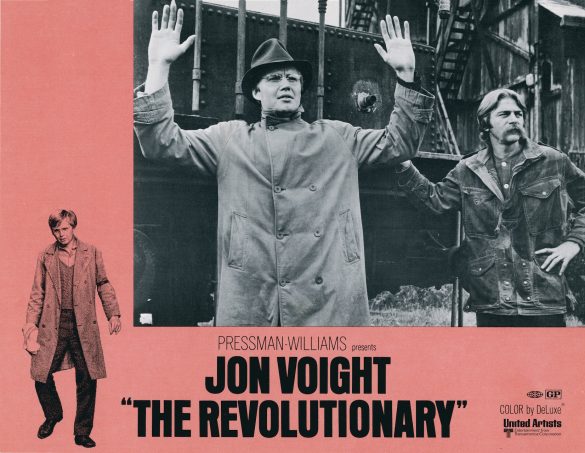

Williams wanted to make a comedy next but Pressman handed him a copy of Hans Koningsberger’s novel The Revolutionary and Picker agreed to finance an adaptation (credited to Koningsberger but much reworked by Williams and Voight, the film’s star). He told Williams, à la Monroe Stahr, that UA should make a film every year that loses money. The Revolutionary certainly bombed, but it’s also one of the most intelligent representations of that era’s student protest. Williams’s sympathetic portrayal is of an idealistic but bumbling young student – known only as A – as he wanders in a fog of bewilderment, in search of a viable ideological course of action, undergoing some kind of political evolution. He’s a dud at being a revolutionary, which the film makes clear is a lifestyle – a drab one at that. A’s digs, and the nondescript industrial London where the film was shot, are dingy. “Most of his ostensible revolutionary activities… are in fact ones of great drudgery, such as stapling propaganda handouts,” Williams said of the seediness of the enterprise. “Rebellion, like war, consists mainly of waiting around,” wrote Koningsberger.

The myopic A fails to commune with an Old Left labor organiser (Robert Duvall, in between Altman’s M*A*S*H and Lucas’s THX 1138), and is disappointed when he’s released from jail before he has a chance to recite to a judge a political tract he has written, at which point he decides he’s better off chasing girls. He copies from a magazine his best lines for a love letter, and after taking to graffitiing slogans on walls nearly gets beaten up. When the cops move in and A is finally flattened, he limps back to the parental bosom, says hello to the maid, has a drink, and refuses his father’s offer to save him from the draft (a phone call could be made). His most radical act is performed in cahoots with self-destructive brigand Leonard II (Seymour Cassell, doing Abbie Hoffman), who burns money in public: they bust open a pawn shop and enable people to reclaim their property for free, then skedaddle when the cops come. A giggles as they depart, taking no responsibility, leaving everyone to their fate.

He’s too conflicted and full of self-doubt to make a real impact. Williams abstracts the remorseless world through which he moves, and London becomes an indeterminate setting that can pass for anywhere in the Western world between 1900 and 1969. It’s more Dostoyevsky than SDS, more Mario Monicelli’s The Organizer than Robert Kramer’s Ice – all with a twist of Beckett. (Koningsberger’s novel is a throwback to an unspecified time and place where police carry “portraits,” not photos, the poor die of tuberculosis, streetlamps are being converted from gas to electricity, and A sleeps on straw.) The film’s timeless, placeless emphasis is one reason it has aged so well. In an era of social media and mass persuasion, of vulnerability and susceptibility, A’s impressionable nature takes on new meaning.

Even with a fuller budget, Williams retained an understated storytelling style – static, direct, few close-ups. The cinematographer was Brian Probyn, whom Williams later suggested Terrence Malick – Harvard ’65 – hire for Badlands. Herbert Smith, veteran camera operator, had worked on a batch of Ealing films, including Alexander Mackendrick’s Whisky Galore! Images under the opening credits (Berlin 1848, Paris 1870, Saint Petersburg 1917, Paris 1968) include photos taken by Williams in Chicago in August 1968. Despite the poetic license, the distantiation from the United States, The Revolutionary is obvious in its intent. 1970 was the year Frank Shakespeare, head of the United States Information Agency, insisted that too many American films playing at the Sorrento festival – Ralph Nelson’s Soldier Blue, Sam Peckinpah’s The Ballad of Cable Hogue, Robert Downey’s Putney Swope, Haskell Wexler’s Medium Cool and The Revolutionary – were “dedicated to social aberration” and didn’t reflect the mores of “true America.”

The Radical Committee, the bland group with which A is affiliated, picks him to hand over a bribe to a commissioner in the justice department. A is hesitant – he intuits that this is a wildly unrevolutionary act – “You’re just being digested into the system!” – and when he does end up sitting across a desk from this official time stands still, until A finally cottons on and whips out the wad of cash he brought with him, at which point, like a slot machine, the man lights up and swiftly concludes the meeting. For what is there to say? The ideas, the arguments – it’s all irrelevant. Power is money. A surreal moment, but implies Williams, no more than the fact that when The Revolutionary was filmed, hundreds of American soldiers were dying every month in Vietnam. “Corruption at its most pure,” as Williams puts it, “has a touch of absurdity to it.”

Politics were moving so quickly, not even the quickest of filmmakers could grab hold. (The Newsreel participants of Ice held up the film’s release because they felt it no longer represented their shifting political viewpoint.) Ernest Callenbach, referring to the killing of judge Harold Haley and three others in August 1970, noted in Film Quarterly that The Revolutionary’s climax – the attempted assassination of a judge – had been “outpaced.” As with Out of It, the built-in lag between inspiration and finished product muted any commercial prospects. Williams’s drama was behind the times. There is no bravura student/cop-clash climax – one reason why Stanley Kramer’s R.P.M. (sociology prof as well-meaning but hopeless hero), Stuart Hagmann’s The Strawberry Statement (camera angles galore, zero political depth, musical interludes in lieu of any drama), Richard Rush’s Getting Straight (entertaining Elliott Gould as worn out, ex-politico grad student), and Art Napoleon’s The Activist (fiction/doc B-movie hybrid starring a real-life veteran of the Free Speech Movement) are all inferior to Williams’s version of events. He has something bigger in mind. With a kind of dramatic sleight of hand, and very much with Voight’s assistance, Williams tells a story of profound introspection. A, buffeted and unmoored, drifts almost in a fugue state. Deepest fears are vividly visualised in the film’s final seconds. Praxis is one thing – but actually throwing a bomb? That kind of choice would paralyse most of us. Audiences in 1970 might already have been well convinced of the value of revolution, but what were they prepared to do about it? The Revolutionary wasn’t what radicals who had already taken to the streets wanted to see. As infuriating as Williams showing that A has perhaps lost his nerve is the suggestion that he is being set up by nefarious leftists.

Shortly after finishing The Revolutionary, a politicised Williams experienced a real-life rendition of A’s angst. Should he follow through on a documentary about Black Panther Eldridge Cleaver? The fundraiser was made irrelevant midproduction when, during turbulent filming in Algeria, Williams was told about the impending kamikaze Flash of Lightning attack. “Your job in New York is to identify and locate power stations,” Cleaver told him. “And figure out possible locations for field hospitals.” So, what is Williams prepared to do? He backs away, after having promised the Panthers $17,000 in cash, which is handed to Chief of Staff David Hilliard in a New York hotel bathroom. Interview material of Cleaver filmed in Algeria is abandoned in a Paris airport locker.

Neck deep in Panther affairs, and with the authorities sniffing, a jittery Williams accepted a new directing gig, the production of which offered a welcome opportunity to leave behind New York’s political pressures. Dealing: Or the Berkeley-to-Boston Forty-Brick Lost-Bag Blues was adapted from a new novel by brothers Michael (Williams’s Harvard pal, later author of Jurassic Park) and Douglas Crichton (writing collectively as “Michael Douglas”). Williams wasn’t enthusiastic about making another film (“Movies are some kind of never-ending cycle, a trap of some kind”), and, years after Dealing’s release he was still knocking it, suggesting “it was probably most accessible to functioning schizophrenics.” But this hip, genre-hinting, comic caper set at Harvard has much going for it, including a jazzy score by Michael Small (his music for Out of It and The Revolutionary is exceptional; later scores include Alan Pakula’s The Parallax View and Arthur Penn’s Night Moves), a typically restrained camera style, and an early performance by John Lithgow, as a budding drug kingpin scumbag cum experimental theater director.

There is great chemistry between Robert Lyons (Peter) and Barbara Hershey (Susan) – a Harvard undergraduate in love, desperate to reconnect with the girl of his dreams, whom he meets on a drug run from Cambridge to Berkeley and back again in a single day. Their banter, as they stroll (in a single shot, on a long lens) through the zoo, him “in disguise” (think Richard Burton in The Spy Who Came in From the Cold), is another kind of absurdist hilarity, and feels like a dry run for Coppola’s The Conversation. The film’s sensuous sex scene – only two shots lasting nearly three Warholian minutes – opens with coke-sniffing foreplay. Susan is busted and booked for only twenty bricks of dope when in fact she left Berkeley with forty. Peter smells a rat. Way over his head, what is he prepared to do to save his girl? He jumps into action, in search of dirty Boston cops, which precipitates a shoot-out climax at Walden Pond. Richard Corliss in Films in Review described Dealing as a “natural blend of two well-worn movie genres” – the “youth” film and the “drug heist” film (The French Connection had come out the year before). Williams compared it to a Hardy Boys adventure. That resonated, and opening weekend was a smash. But it didn’t last long. “I thought many more people were smoking pot back then than actually were,” explained Williams in 1979.

There is great chemistry between Robert Lyons (Peter) and Barbara Hershey (Susan) – a Harvard undergraduate in love, desperate to reconnect with the girl of his dreams, whom he meets on a drug run from Cambridge to Berkeley and back again in a single day. Their banter, as they stroll (in a single shot, on a long lens) through the zoo, him “in disguise” (think Richard Burton in The Spy Who Came in From the Cold), is another kind of absurdist hilarity, and feels like a dry run for Coppola’s The Conversation. The film’s sensuous sex scene – only two shots lasting nearly three Warholian minutes – opens with coke-sniffing foreplay. Susan is busted and booked for only twenty bricks of dope when in fact she left Berkeley with forty. Peter smells a rat. Way over his head, what is he prepared to do to save his girl? He jumps into action, in search of dirty Boston cops, which precipitates a shoot-out climax at Walden Pond. Richard Corliss in Films in Review described Dealing as a “natural blend of two well-worn movie genres” – the “youth” film and the “drug heist” film (The French Connection had come out the year before). Williams compared it to a Hardy Boys adventure. That resonated, and opening weekend was a smash. But it didn’t last long. “I thought many more people were smoking pot back then than actually were,” explained Williams in 1979.

Dealing, he says, picks up from where The Revolutionary leaves off. “In The Lonely Crowd, David Riesman writes about Tootle – the book Peter reads while sitting on the crapper – about how all little train engines who want to become streamliners must always stay on the tracks. No deviation allowed! Peter is moving from being asleep to being awake. He jumps off the tracks. He has none of the common beliefs of the oppressed masses and doesn’t subscribe to the ethics and morality of the professional class. But he discovers that acting out his selfish motivations isn’t satisfying. The glorification of the self, fame, and fortune – for him it’s all bankrupt. So, what comes next? It’s the eradication of the ego. He drives off into the desert.”

During filming of Dealing, Williams befriended Hershey and her boyfriend David Carradine, who provided him with peyote, his first mind-expanding substance. A transformative experience – building on the hallucinatory state and what Williams calls a “nonordinary realm of consciousness” that, drug-free, had come upon him in a London hotel a couple of years earlier. After Dealing’s release, Williams traveled to the farm outside of Washington D.C. where his Harvard friend Andrew Weil was experimenting with psychedelic MDA, then moved to the West Coast to build a network of filmmakers that the Pressman Williams production company might work with. He became part of a radical political community, at the center of which was Bert Schneider, who introduced Williams to Huey Newton and members of the Weather Underground. At one point Abbie Hoffman, on the FBI’s Most Wanted list, took refuge on Williams’s rural Malibu property. While he was there, Richard Dreyfuss showed up to discuss a script, written by Williams and friend Artie Ross. With a backdrop of waning Sixties idealism, West Coast – a study of “male ego self-immolation,” says Williams – is a loose interpretation of Schneider’s successful attempts to get Newton, awaiting trial for murder, out of the country, to Cuba. A Black hero was unlikely to entice studio financing, so Newton’s story is told via a more palatable Hoffman-like character. “John Calley of Warner Bros. read it, thought it was the most brilliant script he had read in three years,” recalled Williams.

In 1975, the year he won an Academy Award for producing Peter Davis’s Vietnam documentary Hearts and Minds, Schneider traveled with Paula Weinstein, Francis Coppola, Candice Bergen, Lynzee Klingman, Terrence Malick, and Williams to Cuba, where they visited the escapee. Schneider’s cover story, as offered the State Department, was that they were investigating possible U.S.–Cuban film co-productions. Williams’s Super 8mm footage of the journey shows the group’s travels around the island and attendance at a speech by Castro. A photograph in his archive is of Coppola, beaming, next to a surly Fidel.

There was exceptional momentum behind Pressman Williams, which was shaping up to be an important force in independent production. Studio executive Jennings Lang invited the company to operate out of the Universal backlot, and in 1974 a deal from 20th Century Fox was in the offing. There was a film based on a New York magazine article by Gail Sheehy (which became part of her book Hustling), another about the life of Michael Brody, the heir who gave away his fortune, and Bad Marion, an X-rated variation on Last Year at Marienbad, to be shot at The Bronx Zoo. Nicholas Meyer wrote a script about John Wilkes Booth, and a couple of Ross Macdonald adaptations and a remake of Treasure of the Sierra Madre were proposed. There were chances to make Scarecrow and Being There. A list of work-in-progress projects from 1971 includes a feature written and directed by Penelope (Sunday Bloody Sunday) Gilliatt, John Avildsen’s America the Beautiful, Ossie Davis’s Mogul Trident Group, films by De Palma and Dušan Makavejev, a Howard Hughes biopic with Jon Voight (to be directed by Williams), original screenplays by Eleanor Perry and Charles (The Graduate) Webb, a couple of Vonnegut adaptations (Williams wrote a script of Player Piano), and a Scorsese film written by Jay Cocks.

That none were ever made didn’t much bother Williams, who never took any of it too seriously and wasn’t wildly enthusiastic about his studio films – too many flaws, lead characters miscast, scenes missing because of interference, etc. “Another example of the artist alienated from their work,” he says. “The artist always sees how something could be better. But in my case, it really could all have been better.” Even so, while he was making films Williams could well see how the central male character of each, at different stages of life, undergoing transformations of sorts, was his surrogate. (These protagonists, he says, are “not the same, in the sense of his character and personality. But I think that in terms of growth and development, they are all really me.”) James Monaco, who in his American Film Now (1979) describes Williams’s retreat from the business as “the biggest loss” when it comes to comparable examples of unfulfilled promise, noted that his three features represent Williams’ generation “not thirty years later or even ten years later, but uncannily – right in the midst of the swirl of events and passions… Eventually his audiences may catch up with him.”

But none of it, including that kind of praise, mattered much to Williams, who was having a “second childhood” out west. Breaking through personal logjams, ridding himself of certain compulsions, he embarked on a new trip, nudged by a transcendental alchemical experience he had in 1972 in a Colorado motel room – while doing damage control on the set of Badlands, no less. A nine-month-long intensive experience with Oscar Ichazo at the Arica Institute (America without the “me – also a potent influence on Alejandro Jodorowsky’s The Holy Mountain) and an encounter with His Holiness Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, principal teacher of the Dalai Lama, proved life-changing, and Williams continued “floating above the hustle of moviemaking.” Or, at least, moviemaking on anyone else’s terms. The example of the Tibetan mandala, blown into the wind once finished, was the most appealing. As Williams explains, “It’s all a way of fashioning the external world as a reflection of your inner world, of manifesting your being.”

By the end of the 1970s, an awakened Williams had achieved some kind of unity of thought for himself. “I was going to write a book called Gurus, Shrinks and Actors. Gurus in the east know about escaping ego and thought, about quieting the mind to get high. The best shrinks stay empty to retake the patient’s trip with the patient. The actor learns to become thoughtless and to respond with his feelings. When he’s onstage, he’s empty. The only thing that makes him think of anything is the other guy’s line. Gurus, shrinks, and actors are all tuned into the same objective truth.”

Plenty of projects evaporated. The semi-autobiographical After Death is a pre-Ghost variation of the afterlife, inspired by The Tibetan Book of the Dead (“No one was interested at first, and I was tired of huckstering stuff”); a collaboration with former lover Karen Black yielded Breaking Up With Paul, a few scenes of which were shot on 35mm; a script by Jacob Brackman (another Harvard buddy) about mystical practices of Rastafarians was rejected by Bob Rafelson and Schneider’s BBS Productions; Rhinestone Heights was co-written with Helena Kallianiotes (Five Easy Pieces’ fuming hitchhiker) for director Martin Brest; The Unlimited Girl is an update of Schlesinger’s Darling (Julie Christie, that film’s star, is the foundation of Williams’ cinematic myths—he used an image of her, an outtake from Peter Whitehead’s Tonite Let’s All Make Love in London, in Out of It); the adaptation of Carlos Castañeda’s Don Juan books by his mentor Waldo Salt was too expensive to produce (Waldo’s daughter Jennifer, part of the Malibu set Williams ran with, appears in The Revolutionary); a Pope John Paul II biopic by Gandhi screenwriter John Briley fell apart days before filming was to begin; and John Milius’s Apocalypse Now screenplay intrigued Williams but Coppola decided to make it himself. Pressman Williams was dissolved in 1976, around the time Williams turned down Animal House and signed on to direct a (never produced) Paramount adaptation of Luke Reinhart’s The Dice Man. He also said no to Julia Phillips when she offered him Taxi Driver, to Lorne Michaels when he asked for help with a new Saturday evening NBC comedy show he was putting together, and to Jennings Lang, who suggested he make the film of Annie.

A trickle of films did follow. The sentimental Nunzio (1978), set in working-class Brooklyn, is about a simple-minded delivery man-child who runs across rooftops thinking he’s Superman. Played by David Proval (who appears in the hour-long video test of West Coast that Williams produced), innocent, compassionate Nunzio, when confronted by local ruffians, can think of no worse insult than “Up your nose with a rubber hose.” Nunzio, explains Williams, “is a kind of Kaspar Hauser figure, a wholly real and present person, dealing with the neuroses of everyone around him. He’s an empty guy who wants to be of service. The film is an attempt to dramatise the highest state of egoless Buddhist practice.” The unclassifiable Miss Right (1981) is a metaphysical film noir rom-com chamber piece, shot in Rome with Margot Kidder (a decade earlier, Williams had introduced her to De Palma, who directed her in Sisters), Karen Black and William Tepper (star of Jack Nicholson’s Drive, He Said, also the West Coast video, in which he plays a version of Bert Schneider). There were experiments with video through the Eighties and Nineties, scenes written and shot, sometimes with Williams as actor, and features, including The Best Ever (2002), a low-fi digital piece about HIV and tantric sex, and, partly inspired by a reading of Aldous Huxley’s After Many a Summer Dies the Swan, The Amazing Adventure of Marcello the Cat (2007), a kiddie film starring non-lip-synched talking animals (and no humans). Mirage (1995), a cheesy split-personality-Vertigo thriller, is worth a look for Sean Young’s Irish accent, Williams’s turn as a conman with a bizarre green energy scheme open to investors, and Edward James Olmos’s ponytailed, alcoholic ex-cop, who reads Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences, by Williams’s Harvard roommate Howard Gardner, to better get to the bottom of things. The film is another reason to be assured that no matter what the budget, however ludicrous the plot, there is always a compelling flow to Williams’s unambiguous cinema. As a filmmaker he was an audience-pleaser—self-expressive and confident, but never solipsistic. The last frame of one scene always leads smoothly to the first of the next.

Williams’s most important later work is The November Men (1993), a self-funded meta-adventure, written by James Andronica (author of Nunzio), about filmmaker Arthur Gwenlyn, who is dismayed with the paucity of genuine leftist politics. (He’s played by Sanford Meisner-trained Williams, who took acting instruction for years – “I was known for doing things in class that no one else would.”) The film opens with Tom Hayden, still distraught nearly a quarter century after JFK, MLK, and RFK, reporting on the lingering trauma of those murders. Arthur pulls together a group of malcontents, including two aggrieved Iraqis, into a crew/commando unit, and plans to make a film about the shooting of the president. But no one, including his cinematographer girlfriend Elizabeth, is sure whether he really wants to assassinate the most powerful person on the planet or just act it out in front of the camera. “Relax,” Arthur reassures her. “It’s just a movie…”

Today, soon turning eighty and living in a small fishing village in Brazil, Williams considers himself “post-political.” Which is another way of saying – as he does in his memoir – “It’s difficult being a spiritual man in the material world.” He made little money as a filmmaker and was never temperamentally suited to the business. “I was a good photographer and enjoyed it, but being a photographer is different from being a filmmaker. You can be an introvert and a photographer. You can be a forest ranger and a photographer. You can’t be a forest ranger and do my kind of filmmaking.”

In 1971, after divorcing his spectacularly wealthy wife, heiress to the Sears Roebuck fortune (both Girl and The Revolutionary contain scenes of a tentative young man jumping several social classes by entering a home of opulence), Williams walked away close to broke after taking not a penny. He saw behind the veil during those years and was profoundly impacted. Always the empath, he explained in a 1978 interview: “Everybody’s a victim. I’ve known a lot of people in power, and I’ve been around a lot of wealth and a lot of poverty. It seems to me we’re all victims.”

A version of this article appears in the Spring 2023 issue of Cineaste (PDF here).