Abbas Kiarostami

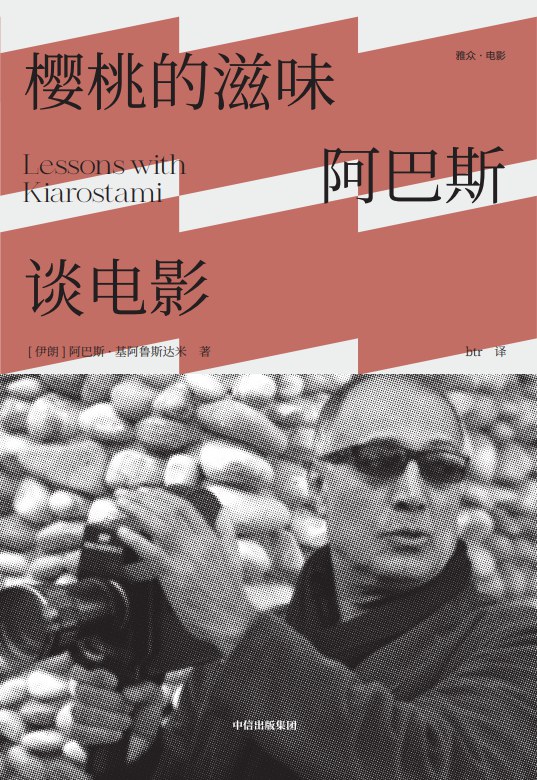

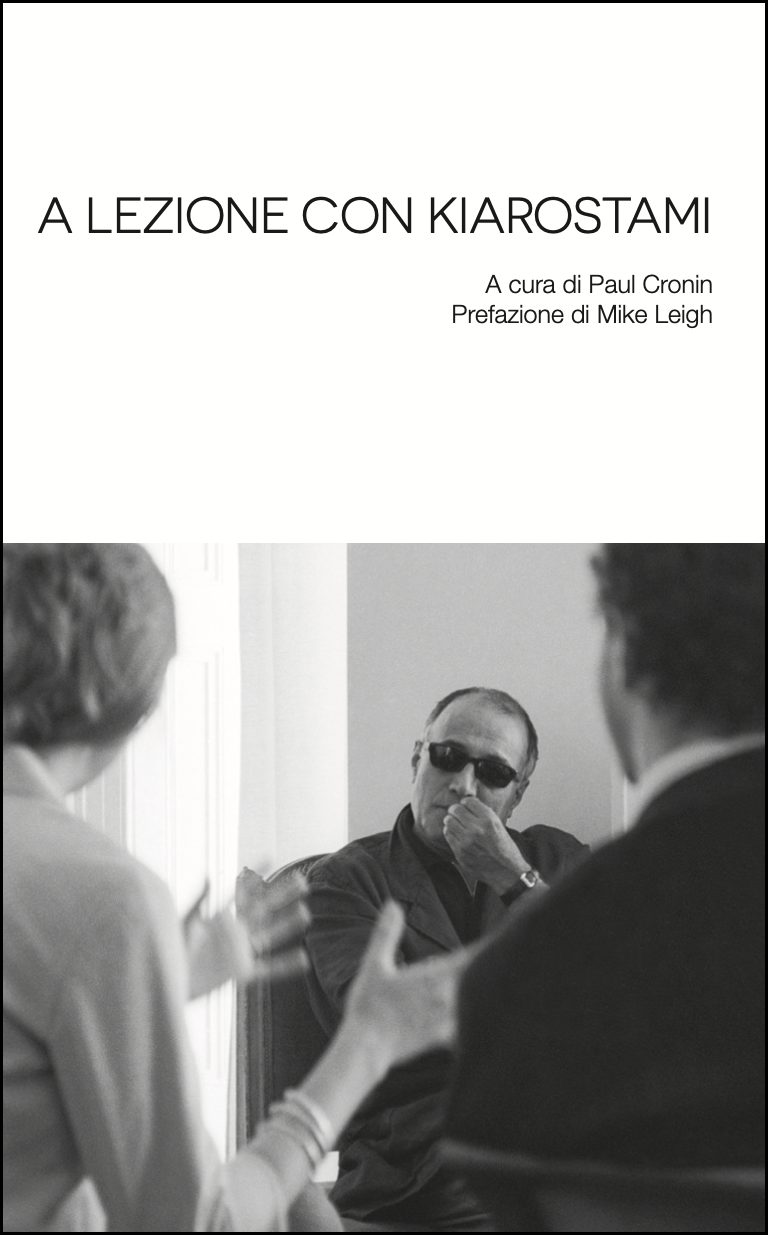

Lessons with Kiarostami (2015) is fashioned from notes made at workshops led by Iranian director Abbas Kiarostami, where he worked closely with young filmmakers, shepherding them and their projects, sending them out with cameras, then screening and discussing the results. Not a traditional interview book or manual of filmmaking, still less a survey of Iranian cinema or study of Kiarostami’s films, Lessons with Kiarostami – which documents a weeklong classroom meeting between teacher and students – is a distillation of his technique and working methods, an attempt to capture the essence of an occasionally elusive experience. Written in the first person, from Kiarostami’s point of view, and with his imprimatur, it details his artful approach to storytelling, his philosophy of life and feelings about the world around him. It is a poetics, a treatise on the creation and meaning of cinema that expresses Kiarostami’s aesthetic sensibility and recounts his orientation towards clarity. Edited by Paul Cronin and with a foreword by Mike Leigh, the book is a piece of the filmmaker trilogy.

Lessons with Kiarostami (2015) is fashioned from notes made at workshops led by Iranian director Abbas Kiarostami, where he worked closely with young filmmakers, shepherding them and their projects, sending them out with cameras, then screening and discussing the results. Not a traditional interview book or manual of filmmaking, still less a survey of Iranian cinema or study of Kiarostami’s films, Lessons with Kiarostami – which documents a weeklong classroom meeting between teacher and students – is a distillation of his technique and working methods, an attempt to capture the essence of an occasionally elusive experience. Written in the first person, from Kiarostami’s point of view, and with his imprimatur, it details his artful approach to storytelling, his philosophy of life and feelings about the world around him. It is a poetics, a treatise on the creation and meaning of cinema that expresses Kiarostami’s aesthetic sensibility and recounts his orientation towards clarity. Edited by Paul Cronin and with a foreword by Mike Leigh, the book is a piece of the filmmaker trilogy.

Lessons with Kiarostami was published alongside bilingual volumes of Kiarostami’s original verse and his adaptations/selections from the Persian canon. These translations are collected together as In the Shadow of Trees. Here for a brochure about the Kiarostami poetry project from Sticking Place Books.

This book, the result of research for Lessons with Kiarostami, contains a large collection of previously published interviews with Kiarostami, including many new translations from French.

Learning not teaching

Monday morning, 9am. AK cuts to the chase. “I have nothing to teach you. I do not want to give you any advice as such. I am merely going to share information with you, and am sure I’ll learn as much as you might this week. What we discuss here and what I say is not good or bad or right or wrong. It’s like going to a psychiatrist: we are just talking. I’m not here to push my own opinions on you. I give you only my feelings. Draw your own conclusions and form your own opinions. My opinions are nothing but my work. In fact, I have to admit that I don’t enjoy teaching that much.”

Regardless, AK then launches into a lecture about his own digital filmmaking methods, using clips from his work, stopping only to pick our brains about the short films we will all be making in the coming days.

Already, even before the end of this first day, I sense AK is anxious about our potential as a group. He knows – as do we – that the only way to learn anything is to do, not just sit here listening. A corner of the room is piled with video cameras while downstairs are four editing suites, ready and waiting for the fruits of our labour.

Two students have an idea for a film which they pitch to the group. AK listens intently, asks questions, then suggests they are ready to shoot. There is no time to waste. “Tomorrow morning,” he says, “take a camera and get filming. Remember, I’m not expecting great work from you. I would rather have a well-made film of only thirty seconds that is truthful and meaningful than a flashy and longer piece that doesn’t tell us much about ourselves. This week might be more about sharing certain experiences than crafting complete stories. Just go out and make something to encourage everyone else.”

Set yourself limits

“In the other workshops I have run,” says AK, “we imposed limitations on ourselves. I remember creative writing class at school. When there were no limitations on our work, no one was able to produce anything. But once a restriction was imposed, everyone wrote something.”

What form should these restrictions going to take? “I have always thought an elevator has the potential to be a good location for a film. Within this enclosed room there is limited space. Presumably films set in elevators have to be of limited time. They make noises, they have flashing lights, some of them even talk to us. People get on and off – perhaps on the wrong floor – which is a good way of introducing characters. The elevator is inevitably something we encounter on the way to other things, places and people. We could even make an action film in a lift by introducing an assassin on the fifth floor and a hero on the ninth. There is the potential for a whole host of activity in an elevator. And travelling in a lift also requires a certain etiquette, which might serve as a narrative device. Simply, I think an elevator could be the setting for lots of small dramas. There will be a unity to these works. They will support each other.”

The ideas start flowing. Every conceivable use for an elevator is considered. There is, inevitably, the suggestion we make a film about how hard it is to make films about elevators. That old reflexive chestnut. AK, ill at ease because of a toothache, discards it out of hand. Someone has picked up on what he said about etiquette. “How about,” says the student, “two people arguing in a lift. When it stops at a floor and someone else gets in, the two people are so embarrassed they stop arguing. There’s an uncomfortable silence for the next three floors. Then the two people leave the lift and immediately continue to argue.” “This is good,” says AK without emotion. “Go now, and shoot.”

Exploit the medium

We are to work with digital equipment. There is no celluloid here. As AK continually suggests, and as his new work Five – a seventy-five-minute film made up of five fifteen-minute single takes – makes clear, form can dictate content. “My film Ten is a couple of years old now,” explains AK, “and today I’m not so fascinated by digital technology. I think this is because recently it has become clear to me just how few people actually know how to use it properly. The problem is that traditional Hollywood film is moving in directions inconsistent with the best digital cinema being produced. This is not easy for smaller filmmakers to fight. The point is that you have to think digitally. When working with an idea, consider that your film could never be made using traditional methods. Could you shoot it with a big 35mm camera or only on a small digital hand-held camera? Shooting Ten on 35mm would have been like taking a wrestler to a 100-metre dash. A wrestler should wrestle, a runner should run. And once you have chosen to use a video camera rather than film – and have chosen it for good reasons – do not compare the quality of the image with any others. Appreciate it for what it is.”

I head with Peter, another student, to a museum around the corner where there are two glass elevators next to each other. Peter in one, me in the other with a camera. I jam the lens up against the glass and shoot as the lift travels up and down. Peter floating past reciting a Shakespeare sonnet. Ten-minute takes. An “art” film of three minutes. I insist on not adding credits or a soundtrack. AK hates it.

Manipulate the actors

Manipulate the actors

“A good feature film is a documentary, and vice versa,” says AK. “When these two come together, we have seen a good film. There is a fine line between tricking actors into doing what you want them to do and letting them improvise. Sometimes during filming on Ten I sat in between the son and mother on the backseat of the car, but most of the time I just let them go and would watch the tape later. I reject the traditional job of the director. This is what the digital camera gives us, this freedom of not having to worry about the reel running out. On Tuesday the son would go swimming, so we arranged for the mother to be late when she picked him up. This meant the son was worried about his swimming race, something that really shows in the film. This was all the directing I did. It’s almost as if the actor becomes the director. The key is choosing the appropriate moment for these actors – none of whom are professionals – to give you something emotional and real.”

Someone asks how AK knows if a non-professional will be able to give him what he needs. “I sit and talk with them,” he explains, “and turn on the camera without them knowing. After seven or eight minutes, once we’ve found our subject, I pretend to turn on the camera. If you see no difference between the moments before and after this flick of the switch, you know you have a good actor.”

One student decides to put AK’s ideas into practice. With his seven-year-old nephew as lead actor, he decides on a little story about a boy demanding payment from those wanting entry to a public lift, to be shot in the block of flats where I live. I am cast as the person who eventually throws him out of the building. For the climax, when I tell the boy to go, the director shoots only my lines. He doesn’t turn the camera around to shoot his nephew’s reactions and dialogue, because he has already spent the morning getting the required close-ups from the boy. By asking him personal questions totally unrelated to the script, a sincere emotional response to my lines was printed to videotape two hours ago, to be intercut with my questions later. The whole thing works beautifully.

Our final day together is spent fine-tuning our elevator films for a public screening at the French Institute’s cinema that evening. The ninety-minute assembly is of variable quality, but on the whole really very good. (“I apologise for calling you all lazy,” says AK.) There are even some truly inventive films that have been made in only two or three days, some in a matter of hours. All are full of a profound humanism. If nothing else, this is what Kiarostami has instilled in us.

A version of this essay appeared in The Guardian, 17 June 2005.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|