Alexander Mackendrick

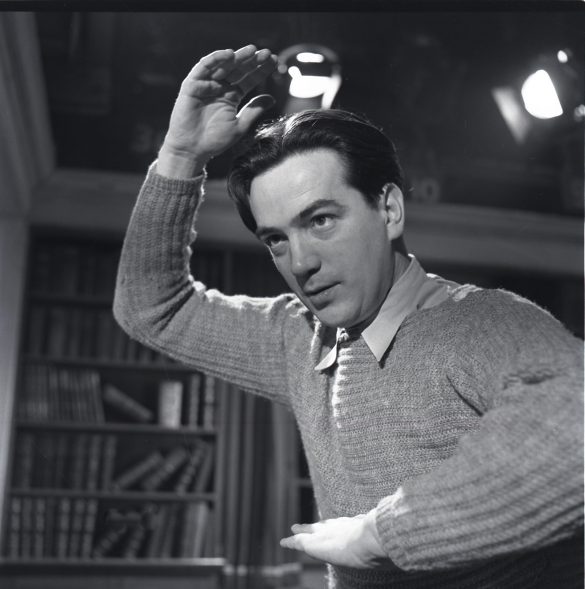

Alexander Mackendrick was one of Britain’s greatest film directors. In the late 1940s he began work at Michael Balcon’s Ealing Studios, where he made some of the most important films of the era, including Whisky Galore!, The Man in the White Suit and The Ladykillers, before directing an authentic Hollywood classic, Sweet Smell of Success, in 1957. After only three more features Mackendrick spent the last twenty-five years of his life teaching film at the California Institute of the Arts, and is today acknowledged as one of the finest instructors of narrative cinema who ever lived.

Alexander Mackendrick was one of Britain’s greatest film directors. In the late 1940s he began work at Michael Balcon’s Ealing Studios, where he made some of the most important films of the era, including Whisky Galore!, The Man in the White Suit and The Ladykillers, before directing an authentic Hollywood classic, Sweet Smell of Success, in 1957. After only three more features Mackendrick spent the last twenty-five years of his life teaching film at the California Institute of the Arts, and is today acknowledged as one of the finest instructors of narrative cinema who ever lived.

On Film-Making: An Introduction to the Craft of the Director (2004) is a collection of Mackendrick’s handouts written for his CalArts students. Edited by Paul Cronin and with a foreword by Martin Scorsese, it guides students through the disciplines Mackendrick called dramatic construction and film grammar (“the narrative and visual devices that have been developed through inventive direction and performing during cinema’s short history”). Sequences from the accompanying audio/visual project Mackendrick on Film (flyer) are here. The book is a piece of the filmmaker trilogy.

Ten books are in progress. The Unseen Observer is a further selection of Mackendrick’s texts conceived for CalArts students, as valuable today as they were when first written fifty years ago. Words on Pictures brings together his articles, lectures, radio broadcasts, letters, notes on films never made, conversations with filmmakers, book reviews and memos. A General Into Battle, a collection of interviews (1950 – 93), is filled with insights into Mackendrick’s nine feature films and teaching career. Italian Journal 1944 – 45 is the essay Mackendrick wrote about his wartime experiences and includes reports he filed while in Rome as part of the Film Production Section of Psychological Warfare Branch. Storytelling is an illustrated anthology of material (1948 – 69) created by Mackendrick for completed and unmade projects, including his penultimate Ealing Studios film The Maggie, his vivid telling of the story of Mary, Queen of Scots, and his adaptation of Eugène Ionesco’s play Rhinocéros. Good Old Sandy, a short assemblage of interviews, describes how film school graduates of CalArts, one of the country’s most experimental art colleges, ended up working on Star Wars, one of the most successful film franchises in Hollywood history. Chances Galore is a two-volume compendium of previously published writing about Mackendrick covering a period of more than seventy years, from reviews of his Ealing films to commentary on the impact of his teaching career and articles reflecting the long afterlife of his filmmaking. Sweet Smell of Success is a facsimile edition of the screenplay, credited to Clifford Odets and Ernest Lehman, that Mackendrick held in his hands while directing his first film in Hollywood, and includes an essay about the various drafts of the script. Accompanying these Mackendrick books are two books by Paul Cronin. Exasperation and Curiosity describes why Mackendrick left behind his filmmaking career and became a teacher, and details his pedagogic philosophy. Walt Disney’s Grand Experiment is a study of the early years of the California Institute of the Arts, from its pre-history to 1975. Also near completion is Celluloid Miles, a three-volume collection of Michael Balcon material (writing, interviews, commentary).

On 17 January 1994, an earthquake shook the San Fernando Valley and decimated the campus of the California Institute of the Arts, just north of Los Angeles. The main damage was due to the intense shaking of the building’s foundations, which caused the mechanical equipment on the roof to slide out of control, pulling piping from its fixtures, shaking books off the library shelves and file drawers out of their cabinets. Papers and books in every room were then doused by the water from the emergency sprinkler system. But everything from the office of CalArts’ faculty member, former film director Alexander “Sandy” Mackendrick – a man who, according to Martin Scorsese, made “some of the best work in the middle of what is now remembered as the Golden Age of British film comedy” – was safe and dry in his garage, a few miles away.

The reason for this is that Sandy Mackendrick, director of the Ealing Studios classics The Man in the White Suit and The Ladykillers, both starring Alec Guinness, and cult Hollywood favourite Sweet Smell of Success with Burt Lancaster and Tony Curtis, had died less than four weeks before (it was said the earthquake was the irascible Mackendrick’s first argument with God). Within days his son had hired a truck, driven to his father’s office, and emptied it of all the papers he could find, particularly those relating to the possible publication of a textbook, including many original drawings and storyboards which hung on the walls of his room. How fortunate for students of cinema around the world that this voluminous archive survived one of the costliest natural disasters in American history, for it provided most of the texts found in Mackendrick’s book On Film-Making: An Introduction to the Craft of the Director. Published thirty-five years after he retired from film directing and became founding Dean of CalArts’ newly established film school, the book is recognised as one of the key texts on the art and craft of screenwriting and film directing.

Today, the consensus is that Mackendrick is one of the finest of all British film directors. Three of his features appear on the British Film Institute’s list of the greatest British films of the twentieth century, and The New Yorker critic Anthony Lane, in his obituary, compared Mackendrick to Fritz Lang and Hitchcock. As a teacher his reputation grows steadily, due to the publication of On Film-Making. So how did one of Britain’s most important film-makers – certainly the most successful and respected of the post-Ealing directors – end up spending the last twenty-five years of his life teaching film in Los Angeles, where he is still revered by former students and colleagues alike?

Arriving at Ealing after the war, Mackendrick was, in his own words, “horrendously spoiled” by producer and studio head Michael Balcon, who had created an environment for writers and directors where they could both learn their craft and earn a weekly pay cheque. Mackendrick directed some of the studio’s most important post-war films, but only a few years later, after Ealing’s demise in 1955 and his move to Hollywood, Mackendrick discovered he had been lulled into a false sense of security. “I found that in order to make movies in Hollywood,” he said in 1990, “you have to be a deal-maker. Not only did I really have no talent for that, I had also been conditioned to have insufficient respect for the deal-makers. I realised I was in the wrong business, and I got out.”

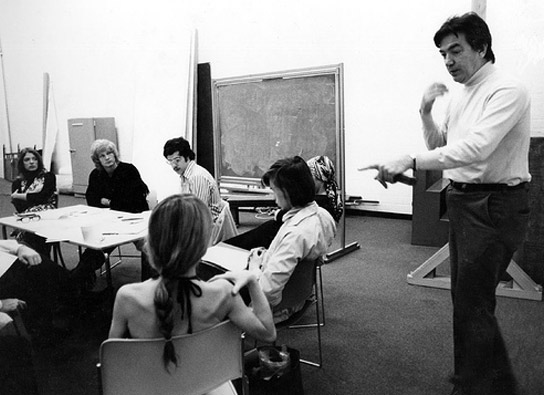

Where Mackendrick went after walking away from the film industry in 1969 – at an age when many would consider outright retirement – was the newly established California Institute of the Arts, which had been funded by the late Walt Disney family. It was at this brand new college that he threw himself into a new career with great fervour, in the knowledge that he would probably never make another film. “It was as a teacher that Sandy found his true métier,” says Mackendrick’s widow Hilary, “and I suspect his remarkable critical faculties were more appropriate to teaching than to film-making. I know his last ten years were his most fulfilling.” As historian Philip Kemp has written, “Mackendrick maintains he never quit making movies – since training future film-makers is an integral part of the movie-making process – but simply stopped directing them.”

Passionately interested in the pedagogy of cinema (“Film writing and directing cannot be taught, only learned, and each man or woman has to learn it through his or her own system of self-education”), he became one of film’s most legendary instructors. Aspirant film-makers from around the world chose to study at CalArts because Mackendrick was there, and even today copies of his carefully composed classroom handouts – which he called “my life’s work” – remain prized possessions among CalArts graduates, who speak of their mentor with veneration. Those who worked with Mackendrick when he was still directing also remember his didactic streak. Oscar-winning screenwriter Ronald Harwood worked with Mackendrick on the screenplay of A High Wind in Jamaica. “Much of what I know about screenwriting I learned from Sandy,” he says.

Mackendrick’s provocative writings are masterful studies of the two primary tasks confronting the film director: how to structure and write the story he wants to tell, and how to use those devices particular to the medium of film in order to tell that story as effectively as possible. Devoid of obscurantism, they concentrate on the practical and tangible rather than abstract concepts of cinema as “art,”‘ and together make up an invaluable book – one of the most important on the subject – even if Mackendrick was himself suspicious of publishing his thoughts on cinema, suggesting that “Talking about film is something of a contradiction in terms: it is already in the wrong medium.”

As any student of screenwriting is aware, there exist a huge number of authors claiming to know the secrets of writing for the cinema. Why Mackendrick’s contribution to this thriving genre succeeds where most fail is that his is a book about film-making (both writing and directing) actually written by a film-maker, a director who had the talent not only to make exciting and lasting works of cinema, but also to articulate with clarity and insight what that process involved. Compared with the overwhelmingly shallow and self-serving publications of most screenwriting teachers, Mackendrick’s lucid and invigorating prose has genuine literary qualities. It also, thankfully, eschews the Believe In Yourself and Maximise Your Creative Powers approach of many how-to-write books. And though written many years ago, it remains fresh and compelling, in part because of Mackendrick’s reluctance to resort to anecdotal tales about his own career. “I can easily imagine a college without a film program building a curriculum around these writings,” writes Martin Scorsese of On Film-Making.

Even more importantly, rather than basing his teachings on an almost scientific analysis of story structure, Mackendrick focused his attention on the structures of cinema itself, those elements that make film such a unique medium of expression, even an “art” (though he was loathe to admit it). As far as Mackendrick was concerned, the technical concerns of film grammar were never to be explored independently of story, while at the same time any competent piece of cinematic storytelling was an inevitable example of how, as he often told his students, “form can never be entirely distinguished from content.”

[youtube d94gXrlDcNY nolink]

Mackendrick was keen to emphasise that everything in a film should be at the service of the narrative, whether lighting (“What mood and emotional tone can be established through the use of light and shadow?”), editing (“If I cut here, what will be revealed to the audience, what will be left out, and how will this help tell the story?”), framing and shot size (“If I use a close-up here rather than a long shot, what am I asking the audience to think about?”), camera movement (“If I move the camera, from whose point of view will the audience be experiencing the action?”), or acting (“How can I use this prop to convey a particular story beat to the audience without saying anything?”). “Every bit of a film,” explained Mackendrick in 1953, while still at Ealing, “ought to be a necessary part of the whole effect.”

The critical link between his “dramatic construction” and “film grammar” classes was his passionate belief in the collaborative nature of film-making, something often lost on auteur-driven film students (or hyphenates, as Mackendrick called them, those who insist on being “writer-directors”). He felt it was vital that the screenwriter understand, at the most fundamental level, the medium he is writing for. “A true movie,” wrote Mackendrick, “is likely to be 60% to 80% comprehensible if the dialogue is in a foreign language.” A story told in shot-to-shot images with imaginative use of camera movement, lighting and sound, and also through the actor’s ability to take advantage of props and costumes, is likely to be more memorable than a dialogue-driven screenplay, suggested Mackendrick. As such, his students studied what he called the “pre-verbal language of cinema,” those conventions laid down by the silent film-makers in the first few years of the twentieth century. One of his most entertaining and important handouts is “Cutting Dialogue,” in which Mackendrick describes re-writing a scene of a dozen dialogue-filled pages, ultimately trimming it to a mere four words, though remaining “absolutely faithful to the playwright’s original story.”

Mackendrick retired as Dean at CalArts after ten years, but spent the rest of his career teaching. He gave students not only a solid grounding in the nuts and bolts of writing and directing, but also ensured they had a healthy perspective on the industry they hoped to enter, and many of his ideas about cinema are equally applicable to other realms of creativity. Writer-director James Mangold, Mackendrick’s best known student, has said of his teacher, “If I turned in a ten-page short film script, Sandy would come back the next day with eleven pages of handwritten notes. I think the most important thing he taught me was just how much hard work goes into film-making. He was leading by example of industriousness.”

“I wake up every morning with an eager mixture of exasperation and curiosity,” declared Mackendrick in 1977. “I’m not sure I have any answers. If I do have anything it’s an instinct for how to organise the questions.” How fortunate we now, fifteen years after his death, are to have his perceptive questions – and his even more enlightening answers – contained between the covers of a single, unique volume.