Peter Whitehead

Peter Whitehead made the first Rolling Stones film, filmed Allen Ginsberg at the Albert Hall, was the first person to publish a Jean-Luc Godard script in English, made the quintessential Swingin’ London film, was inside the occupied buildings of Columbia University with a camera in 1968, and filmed the pop promos and concerts of Syd Barrett, Pink Floyd, Nico, Jimi Hendrix and Led Zeppelin. After leaving filmmaking behind, he authored several novels and for years lived in Saudi Arabia, where he ran the world’s largest private falcon breeding sanctuary.

Peter Whitehead made the first Rolling Stones film, filmed Allen Ginsberg at the Albert Hall, was the first person to publish a Jean-Luc Godard script in English, made the quintessential Swingin’ London film, was inside the occupied buildings of Columbia University with a camera in 1968, and filmed the pop promos and concerts of Syd Barrett, Pink Floyd, Nico, Jimi Hendrix and Led Zeppelin. After leaving filmmaking behind, he authored several novels and for years lived in Saudi Arabia, where he ran the world’s largest private falcon breeding sanctuary.

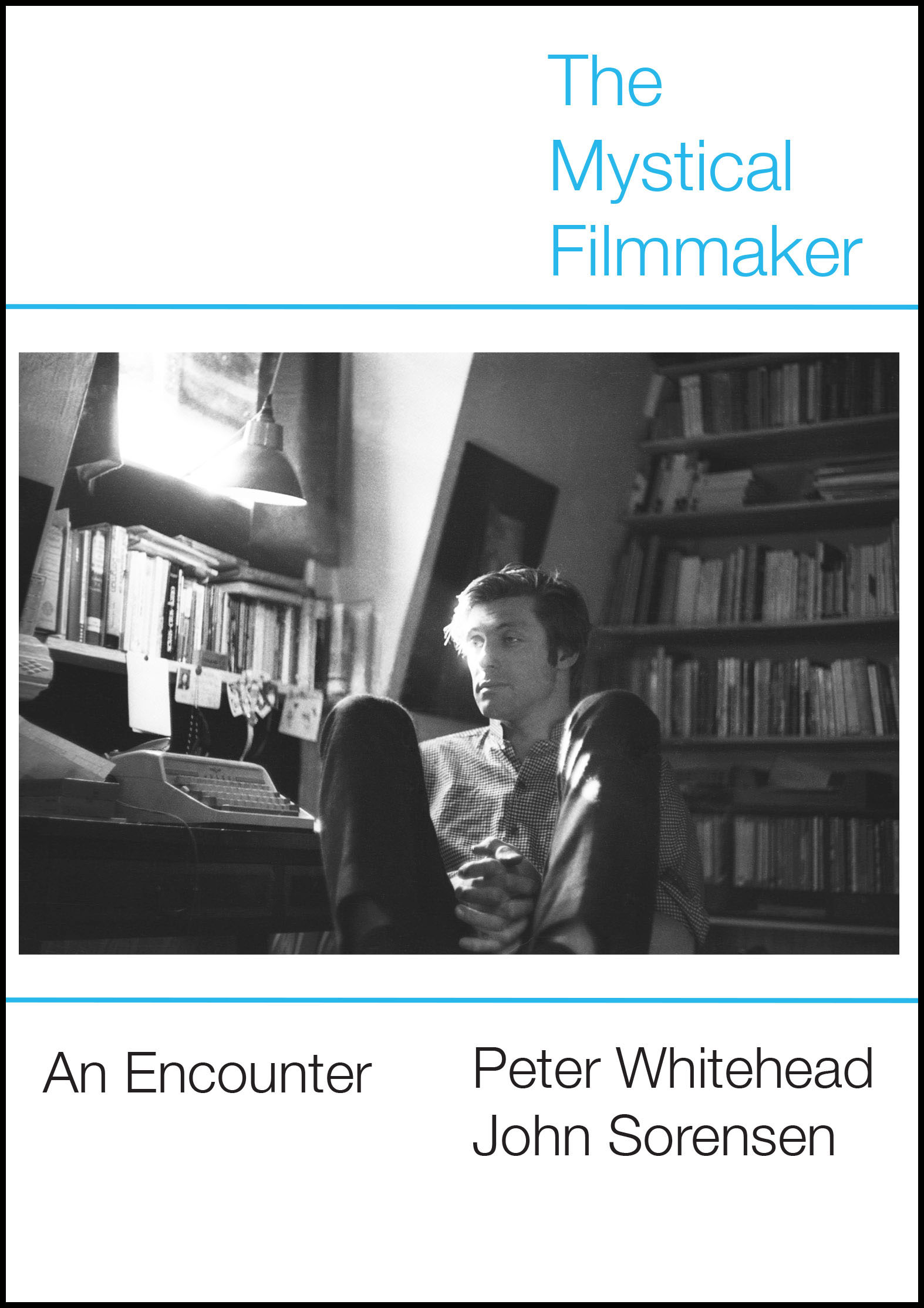

In the Beginning was the Image accompanied the 2006 retrospective of Whitehead’s films (seen at archives and festivals worldwide, including the Viennale). Watch it alongside two sister projects – Once out of nature… (2007) and Fool that I am… (2015) – here. Dialogue transcripts of the three films: here, here and here. Things Fall Apart (2011) is a two-volume collection of writing (here and here) by and about Whitehead, co-edited by Paul Cronin. The Mystical Filmmaker, correspondence between Whitehead and John Sorensen, was published in 2015 by Sticking Place Books. A piece of the 1968 trilogy.

O world invisible, we view thee,

O world intangible, we touch thee,

O world unknowable, we know thee,

Inapprehensible, we clutch thee!

Francis Thompson, “In No Strange Land”

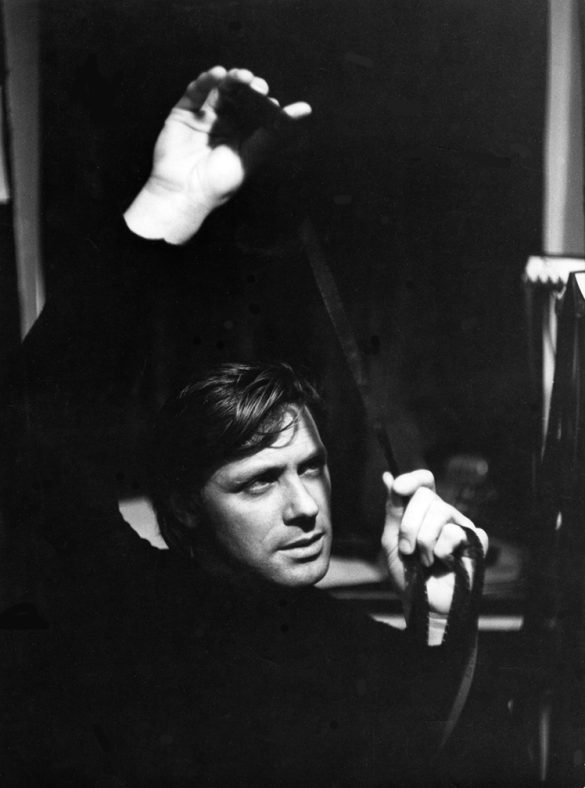

Edinburgh, Summer 1969. British director Peter Whitehead is attending the film festival to present The Fall, his semi-fictional take on the collapse of legal protest against the Vietnam War in the United States. Shot in New York, the film details the city’s highs and lows during one of the most troubled moments in modern American history and is Whitehead’s most ambitious effort to date. In the preceding four years he has made a handful of now legendary films. The spontaneous Wholly Communion documents Allen Ginsberg’s incendiary 1965 poetry reading at the Albert Hall. Charlie is My Darling, starring the startlingly unguarded Rolling Stones, remains one of the finest examples of British vérité ever made. Benefit of the Doubt is Whitehead’s version of the Royal Shakespeare Company’s kaleidoscopic 1966 outburst against the Vietnam war US, as directed by Peter Brook. And Tonite Let’s All Make Love in London is at the same time the quintessential Swingin’ London document and a dark vision of a city at war with itself.

Whitehead is apprehensive about audience response to his complex new work. Two years in the making, The Fall has not only almost bankrupted him, it precipitated a nervous breakdown during editing. To calm his nerves he wanders through town before the screening and finds a quiet leafy square lined with benches where he takes refuge.

“I suddenly heard a noise behind me, a twittering and fluttering. It was like a Hitchcock film. Hundreds of birds were flying behind me. Then I heard a strange shuffling sound, and around the corner walking very slowly comes a little old man. He stops about three yards from me, pulls something out from his pocket and shouts. ‘Charlie! Where are you?’ Then I see a bird fly down, and the man takes his hand away saying, ‘Not you! You wait. Charlie!’ Charlie comes down, sits on his finger and eats. ‘Now you Rose. Where are you?’ And Rose flew down. He was there for half an hour, feeding all the birds, one by one, by name. I sat there, utterly stunned by what I was seeing. At that moment I realised I would sooner have this old man’s talent than the talent to make The Fall, so I quit filmmaking, bought my first falcon for £8 and spent twenty years living in some of the most remote and beautiful places on earth.”

Whitehead did pick up the camera after his Edinburgh epiphany. He shot and edited the magnificent Led Zeppelin concert at the Albert Hall in 1970, as well as Daddy with French sculptress Niki de Saint Phalle in 1973 and later Fire in the Water with Nathalie Delon, something like a greatest hits collection. But for the dashing young director, 70 this year, the filmmaking, which had always only ever been experimentation, was essentially over. Whitehead’s subsequent solitary travels as a falconer in the deserts and atop the mountains of Asia and the Middle East might appear antithetical to his first conspicuously colourful thirty-two years, where he played the role of the ubiquitous cameraman documenting the bright lights and urban commotions of the era. But his need to explore, to seek, to move on, was always within, latent, waiting to erupt.

Peter Whitehead, New York, April 1968

Born to a working-class family in the Liverpool slums, Whitehead, from the start an academic over-achiever, was selected by Atlee’s welfare state to be educated at the hands of the public school system. “As a working-class lad my father died on me at an awkward age, according to Freud’s theories. But the government coughed up and sent me to a very privileged public school where I got the best education in the country, and where – thanks to a natural gift for memory – I was able to surpass everybody else and get a scholarship to Cambridge. The problem is I was educated to be posh, never actually being able to come to terms with the fact that I can never feel at home anywhere.”

As a young man, two encounters with Egyptian mythology affected Whitehead deeply. At the Louvre aged seventeen he was possessed by a statue of Horus, the falcon-headed shaman. Later at Cambridge, where as a student of physics and crystallography he worked as an assistant to Crick and Watson, Whitehead wandered into the Fitzwilliam Museum. Drawn down into the Egyptology department he was again captivated by a small sculptured head of Meritaten, the daughter of Akhenaten and Nefertiti. It was also at Cambridge, after seeing Bergman’s The Seventh Seal, that he became, in his own words, “ripe for shamanistic possession.” His rebirth, years later, in an unassuming Scottish square, was a return to these passions.

Whitehead, who after Cambridge won a scholarship to the Slade School of Fine Art, might be the only student to attend that college who never painted a single picture. On his first day he walked through the studios, looking at the work of other students, and quickly realised “I wasn’t an artist.” Ending up in the office of newly installed head of film, respected director Thorold Dickinson, Whitehead – an autodidact when it came to all facets of filmmaking – started shooting 16mm films around the corridors of the Slade and before long was working as a documentary cameraman for Italian television. Soon after graduation he made his first film, The Perception of Life, shot almost entirely through a microscope, a process that helped solidify his belief that non-fiction cinema had nothing whatsoever to do with objective truth.

The opportunity to make what became Wholly Communion came after Whitehead attended a reading by Ginsberg in a London bookshop, after which he volunteered his services as a cameraman should the mooted Albert Hall event take place. A week later, after borrowing £90, Whitehead found himself standing before seven thousand people, listening to Corso, Fainlight, Ferlinghetti, Trocchi, Ginsberg and others, trying to thread film into a camera he didn’t know how to use properly. He eventually ended up with forty minutes of film and an unusable soundtrack. Discovering the BBC had recorded the readings, Whitehead spent days synching sound to image, constructing a dynamic thirty-three minute film that documents the opening volley of the British counterculture movement.

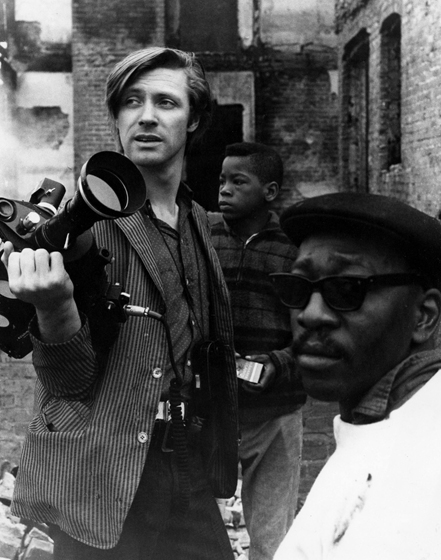

Peter Whitehead, New York, 1967/8

Wholly Communion helped lay the groundwork for Whitehead’s next three projects. Rolling Stones manager Andrew Oldham saw the film and, curious about the new possibilities of lightweight cameras and sync sound, telephoned Whitehead. “He asked if it were possible to make a film without lights and with a small crew, then offered me £2000 pounds to make a film about the Rolling Stones. I think he just wanted to know what they looked like on film, which was actually pretty good.” Shot over two days during the Stones’ mini-tour of Ireland, Charlie is My Darling led to Whitehead following the group to New York where he made the classic promo “Have You Seen Your Mother Baby” featuring the boys in drag. Whitehead later conceived the infamous “We Love You” promo, shot the day before Jagger and Richards’s appeal for possession of marijuana was to be considered (they were let off). With Mick as Oscar Wilde, Marianne Faithful as Bosie, and Keith as a High Court Judge, the BBC promptly banned the film. Whitehead was soon shooting clips for Top of the Pops, and pioneered the form through his work with Nico, The Shadows, The Dubliners, Eric Burdon and the Animals, Jimi Hendrix and Pink Floyd.

Peter Brook then asked to screen Wholly Communion and Charlie to his RSC actors who were devising what would become US. One of the writers of Brook’s theatrical experiment was poet Adrian Mitchell, who at the Albert Hall the year before had recited his devastating “To Whom it May Concern” (“I was run over by the truth one day/Ever since the accident I’ve walked this way/So stick my legs in plaster/Tell me lies about Vietnam”). Invited by Brook, Whitehead spent a day filming with the company at the Aldwych Theatre. In between his vibrant colour footage of the production’s more physical scenes are monochrome interviews with actor Glenda Jackson and Brook himself, who at a press conference suggests the chances of a piece of theatre affecting government policy is “absolutely nil,” thus foreshadowing Whitehead’s feelings of irrelevance when it came to The Fall a few years later.

Whitehead took the title of Tonite Let’s All Make Love in London from Ginsberg’s poem “Who Be Kind To,” written especially for the Albert Hall event. “With Tonite I wasn’t spoofing what was going on. I was trying to examine the mythology that everybody in London was having fun. Ginsberg’s poem, which is very much about the theft of British culture by American cultural and capitalistic imperialism, is actually very dark. For me the Sixties was the Aldermaston march, the war in Vietnam and the Dialectics of Liberation. The only miracle about those years is that it was a moment of extreme change that managed to get through without savage violence.” Whitehead’s antagonistic feelings toward “the 60s” – and America – were to lead him straight into the belly of the beast. “There seemed nothing more to film in London except my boredom, despair and apathy,” he wrote in 1969. “All the movements seemed to be dead. The beat, hippie, underground, pop scenes had all become indulgent or fashionable. If something was to be done, by me or anyone, it would not be done in ‘America-owned’ England.”

The Fall, filmed between October 1967 and June 1968, is a remarkable example of the kind of self-reflexive film that was so potently influencing non-mainstream cinema at the time. Immediately after attending the New York Film Festival, where he presented Benefit and Tonite, Whitehead started shooting protest meetings, pro-war rallies, poetry readings and public performances. Seeking to impose some kind of structure on these hours of material, he devised a fictional story about political assassination into which could be incorporated the documentary footage. The result is an astonishing hybrid of fiction and non-fiction, a subjective take on the American Left and its confrontation with the power elite that was waging war on Vietnam. “What I was actually filming was the collapse – the ‘fall’ – of an increasingly ineffective and impotent protest movement,” Whitehead explains. “As a group, the anti-war activists were fragmenting, crossing some kind of threshold, tipping over into something more radical. The breakdown of legal protest and the shift to calculated political anarchy was just around the corner.” In April 1968 the students of Columbia University took control of several buildings on campus, prompting Whitehead to dash uptown where he spent five days and nights filming alongside them. His driver would pick up the exposed film – lowered in a bucket from a window – and take it to the laboratory. When several reels were mysteriously ruined during processing, Whitehead was certain the FBI were after his footage, and following the violent struggle between students and police that ended the university occupation, Whitehead flew to London, feeling lucky to have escaped intact. At Heathrow Airport he discovered that Robert Kennedy, with whom he had been filming with only three weeks before, had been shot. Whitehead slowly pieced himself back together by sitting for months in front of his Steenbeck, making sense of the sixty hours of footage he had collected.

The Fall, filmed between October 1967 and June 1968, is a remarkable example of the kind of self-reflexive film that was so potently influencing non-mainstream cinema at the time. Immediately after attending the New York Film Festival, where he presented Benefit and Tonite, Whitehead started shooting protest meetings, pro-war rallies, poetry readings and public performances. Seeking to impose some kind of structure on these hours of material, he devised a fictional story about political assassination into which could be incorporated the documentary footage. The result is an astonishing hybrid of fiction and non-fiction, a subjective take on the American Left and its confrontation with the power elite that was waging war on Vietnam. “What I was actually filming was the collapse – the ‘fall’ – of an increasingly ineffective and impotent protest movement,” Whitehead explains. “As a group, the anti-war activists were fragmenting, crossing some kind of threshold, tipping over into something more radical. The breakdown of legal protest and the shift to calculated political anarchy was just around the corner.” In April 1968 the students of Columbia University took control of several buildings on campus, prompting Whitehead to dash uptown where he spent five days and nights filming alongside them. His driver would pick up the exposed film – lowered in a bucket from a window – and take it to the laboratory. When several reels were mysteriously ruined during processing, Whitehead was certain the FBI were after his footage, and following the violent struggle between students and police that ended the university occupation, Whitehead flew to London, feeling lucky to have escaped intact. At Heathrow Airport he discovered that Robert Kennedy, with whom he had been filming with only three weeks before, had been shot. Whitehead slowly pieced himself back together by sitting for months in front of his Steenbeck, making sense of the sixty hours of footage he had collected.

Whitehead’s American experience, specifically his time inside “the perfect microcosm of America,” Columbia University – where he was finally able to participate with the rebellion rather than just sit on the sidelines filming it – was the culmination of all he had been pre-occupied with as a film-maker for the previous few years and at the same time the event that detached him from everything. “I sometimes wonder if all my films, especially the last two, aren’t acts of aggression against film, against limits put on me by the nature of film itself,” he wrote in 1968. “The outside world no longer seems worth looking at, so you have to turn inwards.” Today Whitehead fully understands what happened to him back in 1968. “I was continually asking myself if I was being an activist by making The Fall. The question was: could I change the world by making the film? When I realised the answer was no, I gave up filmmaking and decided to change myself instead.”

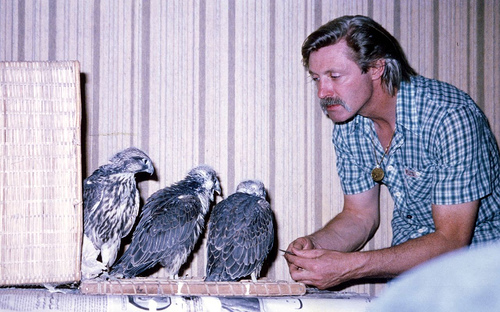

Peter Whitehead, Saudi Arabia, 1980s

The way to do this, Whitehead sensed, was a return to nature. “I had reached a point where I couldn’t do anything without relating it to the possibility or necessity of filming it. I couldn’t walk past a person or a shop window without thinking they could be filmed. I couldn’t read the newspapers in the morning without wanting to go off and film what I was reading about. I was going crazy, constantly zooming and panning and editing with my eyes and ears. Having discovered that the film camera was the very thing severing me from authentic existence, I went off into the wilderness. When you’re hanging on a cliff ledge three hundred feet over the Atlantic Ocean in north Morocco, not sure whether to go up or down, or when you’re fifty miles north of the Arctic Circle in temperatures of minus thirty degrees trying to trap one falcon with a territory of twenty square miles, you don’t stop to take photographs. In the end I spent twenty years of my life relating to falcons, breeding them, travelling thousands of miles with their eggs on my stomach, hatching them here in my garden and bringing up the chicks. That’s authentic stuff. I’ve never known such ecstasy as when I said to myself, ‘I don’t want to make any more films.'”

Escaping from the West and its post-60s disappointments and political reversals, Whitehead spent years wandering through Afghanistan, Alaska, Algeria, Iran and Morocco – including a transformative experience working with a Pakistani shaman in the 1970s – before realising he was more concerned with saving endangered species than just flying birds. In 1981 he accepted the patronage of Prince Khalid al Faisal of Saudi Arabia and together they built the world’s largest private falcon breeding centre atop Al Soodah, the country’s highest mountain. For ten years Whitehead honed his technique of breeding birds in captivity by imprinting them from birth, thus creating for the Saudi Royal Family and its friends an array of falcons. The hours of video footage of Whitehead practising his courtship rituals inside the aviaries of the centre – pacing up and down in front of his birds, feeding them live mice, mewing and clucking at them, allowing them to preen his hair – is almost beyond belief.

Never a self-promoter (“I’m an introvert, absolutely an introvert” he wrote in 1969 – nothing seems to have changed), Whitehead has always been an outsider, something that from the start of his filmmaking career equated to a paltry distribution of his work. His cinematic creations have also intersected with history at the most inopportune moments. The day after Whitehead arrived in the United States to celebrate the opening of Tonite Let’s All Make Love in London, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, and during the ensuing riots the cinema where the film was playing shut down. Only days later in May 1968, Benefit of the Doubt – heralded by French critics – opened in a small cinema near the Sorbonne in Paris. The box-office was closed when the attendant was tear-gassed during the student rebellion and the film’s run came to an ignominious end, never to be seen again. After Edinburgh, Whitehead never pushed for distribution of The Fall and to this day it has received only a handful of public screenings. Even though it contains compelling footage of the daily grass-roots protest against the Vietnam war in New York, including unique material filmed inside Columbia, the film was first screened in that city only this year.

Peter Whitehead, Paris, 2007

Fortunately for historians of the era, Whitehead served as producer on most of his films. Unlike many of his contemporaries whose work was made for television and has either been lost or purposely destroyed, the compulsive archivist Whitehead – who so expertly directed, edited and photographed almost all his work – has kept nearly every frame he ever shot in a barn near his home. A cinema obsessive from an early age, at the same time he was making films Whitehead published an array of screenplays though his publishing house Lorrimer Books, including his translation of Godard’s Alphaville and works by Bergman, Renoir and Eisenstein. A prolific writer from even before his Cambridge days, his voluminous archives also contain a plethora of unpublished novels and hundreds of notebooks stretching back to his childhood. In the past ten years Whitehead has self-published six novels, as well as three new full-length fictions recently posted on his website, and this year – in production on his first major film since The Fall – has seemingly come full circle as a film-maker.

“To stand and observe is to be alienated,” Whitehead wrote in 1968. Forty years later, he continues to wander and explore with the intensity that has pushed him, since childhood, from one life to the next.

“I did not go off and eat mushrooms or become a solicitor like everybody else at the end of the Sixties.

I’ve never been on holiday, never wasted a single day of my life. I would consider it a waste if I’m not pursuing my myth in some form or another.”

A version of this article appears in the March 2007 issue of Sight and Sound (PDF here).